Can you imagine knowing that you are right about something very important and that the rest of the world is wrong but will not listen? This is exactly what happened to the Polish astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus. In the 16th century he discovered that the Earth and planets revolved around the Sun. It challenged what people had believed for more than 1,000 years.

NICOLAUS’S EARLY LIFE

Nicolaus Copernicus was born on February 19, 1473, in Thorn (now T oruń), Poland. His family were wealthy merchants and town officials. His uncle, Bishop Łukasz Watzenrode, supported him in his education. Nicolaus started at the University of Kraków in 1491 and studied the liberal arts for four years without receiving a degree. In 1497 he became a Church administrator at the cathedral at Frauenberg (now Frombork). In the same year he went to Italy to continue his education—like many Polish men of his high social class. He studied law at the University of Bologna between 1497 and 1501, and then studied medicine at the University of Padua between 1501 and 1503.

oruń), Poland. His family were wealthy merchants and town officials. His uncle, Bishop Łukasz Watzenrode, supported him in his education. Nicolaus started at the University of Kraków in 1491 and studied the liberal arts for four years without receiving a degree. In 1497 he became a Church administrator at the cathedral at Frauenberg (now Frombork). In the same year he went to Italy to continue his education—like many Polish men of his high social class. He studied law at the University of Bologna between 1497 and 1501, and then studied medicine at the University of Padua between 1501 and 1503.

AN INTEREST IN ASTRONOMY

Copernicu s’s interest in astronomy began while at Bologna, where he lived at the home of a mathematics professor, Domenico Maria de Novara. Together they observed the occultation (the eclipse by the Moon) of the star Aldebaran on March 9, 1497. Domenico Maria was critical of the accuracy of the work of the 2nd-century astronomer Ptolemy. Ptolemy said that the Sun and planets revolved around a unmoving Earth. This idea was generally accepted as true and was strongly supported by the Roman Catholic Church, which was very powerful. Copernicus became more and more unhappy with this view because the evidence of planetary motion did not seem to support it. He began developing his view that the Earth and other planets revolved around a point in space near the Sun. This view would be known as the “heliocentric theory of planetary motion”.

s’s interest in astronomy began while at Bologna, where he lived at the home of a mathematics professor, Domenico Maria de Novara. Together they observed the occultation (the eclipse by the Moon) of the star Aldebaran on March 9, 1497. Domenico Maria was critical of the accuracy of the work of the 2nd-century astronomer Ptolemy. Ptolemy said that the Sun and planets revolved around a unmoving Earth. This idea was generally accepted as true and was strongly supported by the Roman Catholic Church, which was very powerful. Copernicus became more and more unhappy with this view because the evidence of planetary motion did not seem to support it. He began developing his view that the Earth and other planets revolved around a point in space near the Sun. This view would be known as the “heliocentric theory of planetary motion”.

THE SEARCH FOR THE TRUTH

In 1503 Copernicus returned to Poland to take up his administrative duties as canon with the Church. He lived in his uncle's bishopric palace in Lidzbark Warmiński until 1510. The job gave him lifelong financial security and involved no priestly duties. This allowed him the time he needed to study astronomy.

Sometime between 1507 and 1515 he completed a short astronomical essay called De Hypothesibus Motuum Coelestium a se Constitutis Commentariolus (known as the Commentariolus). It was not published until the 19th century. In it he laid down the principles of his new heliocentric astronomy.

After moving back to Frauenberg in 1512, he began his major work called De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres), which brought together all of his astronomical ideas. The book was finished in 1530, but was not published for many years as Copernicus feared criticism from the scientific and religious communities. It was finally printed by a Lutheran printer in Nuremberg, Germany (Lutherans were opposed to the ideas of the Roman Catholic Church). Soon after, on May 24, 1543, Copernicus died at Frauenberg.

REVOLUTIONARY IDEAS

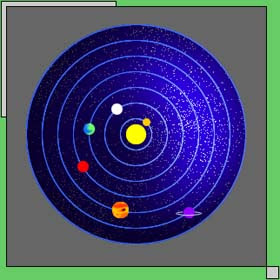

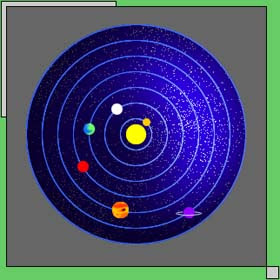

Copernicus's major ideas were that the Earth rotates once a day on its axis (wobbling like a top as it rotates) and revolves once a year around the Sun. Also, the planets encircle the Sun.

This view solved many issues. It explained the apparent daily and yearly motion of the Sun and the stars, and why Mercury and Venus never move more than a certain distance from the Sun (that is because they are closest to the Sun). It also explained the apparent retrograde motion of Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. This last problem, in which the motion of these three planets through the sky appears from time to time to halt and then to proceed in the opposite direction, had puzzled astronomers since ancient times.

The planets could now be placed in their correct positions in terms of distance from the Sun. This was because the greater the time a planet takes to make one circuit around the Sun, the greater the radius of its orbit and its distance from the Sun.

Copernicus did not get everything right. His ideas that the stars are in fixed positions in a sphere at the edge of the Solar System and that the planets had circular and not elliptical (oval-shaped) orbits we now know are wrong.

COPERNICUS’S GREAT INFLUENCE

Copernicus’s ideas were new and revolutionary, and the idea of a moving Earth was difficult for most 16th-century scholars to accept. For many years after his death his ideas were either ignored or rejected. The powerful Roman Catholic Church was particularly hostile—especially to the suggestion that the Earth was no longer the centre of the universe.

One of the first people to openly support Copernicus’s ideas was the German astronomer Johannes Kepler. In the early 17th century, Kepler made precise astronomical studies of the motions of the planets that provided clear scientific evidence to prove Copernicus’s heliocentric view of planetary motion was correct. Kepler’s work was later used by both the Italian scientist Galileo Galilei and the English scientist Isaac Newton. These two men were part of a movement that would later be known as the Scientific Revolution. By the late 17th century the Copernican system was the most widely accepted picture of the universe. Nowadays, we know it to be true.

It is clear that much of what we know today about our world and its place in the universe began with Nicolaus Copernicus.

Did you know?

• The university in Nicolaus Copernicus's home town of Torun, in central Poland, is now named after him.

• Nicolaus Copernicus was not the only famous student of the University of Kraków. Pope John Paul II also studied there.

• Copernicus's first book had nothing to do with astronomy. It was a Latin translation of letters on morals by a 7th-century Byzantine writer, Theophylactus of Simocatta.

• All of Copernicus's astronomical observations were undertaken without the use of a telescope. The telescope was invented in the Netherlands in about 1608, which was 65 years after Copernicus had died.

NICOLAUS’S EARLY LIFE

Nicolaus Copernicus was born on February 19, 1473, in Thorn (now T

oruń), Poland. His family were wealthy merchants and town officials. His uncle, Bishop Łukasz Watzenrode, supported him in his education. Nicolaus started at the University of Kraków in 1491 and studied the liberal arts for four years without receiving a degree. In 1497 he became a Church administrator at the cathedral at Frauenberg (now Frombork). In the same year he went to Italy to continue his education—like many Polish men of his high social class. He studied law at the University of Bologna between 1497 and 1501, and then studied medicine at the University of Padua between 1501 and 1503.

oruń), Poland. His family were wealthy merchants and town officials. His uncle, Bishop Łukasz Watzenrode, supported him in his education. Nicolaus started at the University of Kraków in 1491 and studied the liberal arts for four years without receiving a degree. In 1497 he became a Church administrator at the cathedral at Frauenberg (now Frombork). In the same year he went to Italy to continue his education—like many Polish men of his high social class. He studied law at the University of Bologna between 1497 and 1501, and then studied medicine at the University of Padua between 1501 and 1503.AN INTEREST IN ASTRONOMY

Copernicu

s’s interest in astronomy began while at Bologna, where he lived at the home of a mathematics professor, Domenico Maria de Novara. Together they observed the occultation (the eclipse by the Moon) of the star Aldebaran on March 9, 1497. Domenico Maria was critical of the accuracy of the work of the 2nd-century astronomer Ptolemy. Ptolemy said that the Sun and planets revolved around a unmoving Earth. This idea was generally accepted as true and was strongly supported by the Roman Catholic Church, which was very powerful. Copernicus became more and more unhappy with this view because the evidence of planetary motion did not seem to support it. He began developing his view that the Earth and other planets revolved around a point in space near the Sun. This view would be known as the “heliocentric theory of planetary motion”.

s’s interest in astronomy began while at Bologna, where he lived at the home of a mathematics professor, Domenico Maria de Novara. Together they observed the occultation (the eclipse by the Moon) of the star Aldebaran on March 9, 1497. Domenico Maria was critical of the accuracy of the work of the 2nd-century astronomer Ptolemy. Ptolemy said that the Sun and planets revolved around a unmoving Earth. This idea was generally accepted as true and was strongly supported by the Roman Catholic Church, which was very powerful. Copernicus became more and more unhappy with this view because the evidence of planetary motion did not seem to support it. He began developing his view that the Earth and other planets revolved around a point in space near the Sun. This view would be known as the “heliocentric theory of planetary motion”.THE SEARCH FOR THE TRUTH

In 1503 Copernicus returned to Poland to take up his administrative duties as canon with the Church. He lived in his uncle's bishopric palace in Lidzbark Warmiński until 1510. The job gave him lifelong financial security and involved no priestly duties. This allowed him the time he needed to study astronomy.

Sometime between 1507 and 1515 he completed a short astronomical essay called De Hypothesibus Motuum Coelestium a se Constitutis Commentariolus (known as the Commentariolus). It was not published until the 19th century. In it he laid down the principles of his new heliocentric astronomy.

After moving back to Frauenberg in 1512, he began his major work called De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres), which brought together all of his astronomical ideas. The book was finished in 1530, but was not published for many years as Copernicus feared criticism from the scientific and religious communities. It was finally printed by a Lutheran printer in Nuremberg, Germany (Lutherans were opposed to the ideas of the Roman Catholic Church). Soon after, on May 24, 1543, Copernicus died at Frauenberg.

REVOLUTIONARY IDEAS

Copernicus's major ideas were that the Earth rotates once a day on its axis (wobbling like a top as it rotates) and revolves once a year around the Sun. Also, the planets encircle the Sun.

This view solved many issues. It explained the apparent daily and yearly motion of the Sun and the stars, and why Mercury and Venus never move more than a certain distance from the Sun (that is because they are closest to the Sun). It also explained the apparent retrograde motion of Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. This last problem, in which the motion of these three planets through the sky appears from time to time to halt and then to proceed in the opposite direction, had puzzled astronomers since ancient times.

The planets could now be placed in their correct positions in terms of distance from the Sun. This was because the greater the time a planet takes to make one circuit around the Sun, the greater the radius of its orbit and its distance from the Sun.

Copernicus did not get everything right. His ideas that the stars are in fixed positions in a sphere at the edge of the Solar System and that the planets had circular and not elliptical (oval-shaped) orbits we now know are wrong.

COPERNICUS’S GREAT INFLUENCE

Copernicus’s ideas were new and revolutionary, and the idea of a moving Earth was difficult for most 16th-century scholars to accept. For many years after his death his ideas were either ignored or rejected. The powerful Roman Catholic Church was particularly hostile—especially to the suggestion that the Earth was no longer the centre of the universe.

One of the first people to openly support Copernicus’s ideas was the German astronomer Johannes Kepler. In the early 17th century, Kepler made precise astronomical studies of the motions of the planets that provided clear scientific evidence to prove Copernicus’s heliocentric view of planetary motion was correct. Kepler’s work was later used by both the Italian scientist Galileo Galilei and the English scientist Isaac Newton. These two men were part of a movement that would later be known as the Scientific Revolution. By the late 17th century the Copernican system was the most widely accepted picture of the universe. Nowadays, we know it to be true.

It is clear that much of what we know today about our world and its place in the universe began with Nicolaus Copernicus.

Did you know?

• The university in Nicolaus Copernicus's home town of Torun, in central Poland, is now named after him.

• Nicolaus Copernicus was not the only famous student of the University of Kraków. Pope John Paul II also studied there.

• Copernicus's first book had nothing to do with astronomy. It was a Latin translation of letters on morals by a 7th-century Byzantine writer, Theophylactus of Simocatta.

• All of Copernicus's astronomical observations were undertaken without the use of a telescope. The telescope was invented in the Netherlands in about 1608, which was 65 years after Copernicus had died.

No comments:

Post a Comment